California Opens the Funnel into Civil Commitment -- All the Way

It can't get much broader than 86% of the population--plus dementia commitment, substance use commitment, and more in the news roundup.

States debate whether to commit people for dementia; a new analysis asks if antipsychotics truly help; California broadens the step-one criteria for civil commitment as far as it can go, and recommendations for change emerge from North Carolina and the World Health Organization. All that and more in this selection of some of the interesting and significant stories on civil commitment from April to June of 2025.

15 min. read (or just skim the titled sections)

Ideal vs. Reality (Wtf?!…)

The World Health Organization earlier this year continued to stay true to its ongoing efforts to help re-center civil rights and non-coercive approaches in mental health care systems by issuing a series of modules giving “Guidance on Mental Health Policy and Strategic Action Plans.” Unfortunately, this review from Mad in America notes that the guidance “highlights the discrepancy between many countries’ stated commitments to achieving human rights-based mental health systems, and their widespread failure to implement needed reforms and reallocation of resources.”

So, what’s the reality more like?…

You’re unsettled after an argument with your mother, whom you’ve long had a troubled relationship with. A person posing as a potential client calls and asks you to meet him. Instead, when you pull into the parking lot, a group of strangers appear and surround you. They say you must come with them. They say they’re a mobile crisis team from a local hospital and a psychiatrist is worried about your recent overdose and that you might harm yourself—except that hospital doesn’t have a mobile crisis team and you’ve never heard of the psychiatrist. You explain that you’re feeling fine, and don’t even do drugs. But apparently there’s a caring family member worried about you—and these strangers insist that you come with them.

This is just part of the bizarre story that led to the two-week psychiatric incarceration of Demoree Hadley reported by an NBC News affiliate in Florida. Hadley is suing, but to me, most telling in such cases is the defense that the mental health practitioners and institutions typically provide – saying (truthfully) that all of this is standard practice in civil commitment.

Do you have a story like that one? The Seattle Times put out a call on June 2nd that as of this writing still seems to be valid: "We’d like to hear from people who have experienced involuntary mental health treatment, know someone who has been involuntarily committed, or have worked in the system." I can’t vouch for their reporting, but I know that people who’ve been involuntarily committed or seen it happen to others have helped my own learning curve enormously over the years.

Expanding Civil Commitment: Substance Use (But why?...)

The Canadian province of Alberta has brought in forced treatment for substance users—without any requirement to track outcomes, and despite the fact that even mainstream practitioners are deeply concerned about the practice’s tendency to lead to overdose deaths. While the rationale is that people who use substances are often too “out of touch with reality” to want or seek help, most addiction and mental health practitioners seem baffled by that rationale. They frequently point out that, in fact, countless “patients seeking voluntary treatment...still struggle getting access to detox and longer-term...treatment centres.” This dearth of services exists practically everywhere, yet numerous jurisdictions around North America have been implementing such legislation, anyway. Which leaves the question: Why?

Speaking of Not Helping: Antipsychotics (Do they work?...)

Antipsychotics are, by far, the most common form of forced psychiatric treatment. So I was interested to see that Mad in America publisher and journalist Robert Whitaker put out a summary analysis of what the science has been saying on the short-term effectiveness of antipsychotics. (Disclosure: I often publish in Mad in America, and indeed am currently working on a joint article for MIA and PsychForce Report.)

It’s long been standard for mainstream psychiatry and its most prominent critics alike (including, albeit less strongly, Whitaker himself) to state that, even with all their problems especially over long-term use, there is evidence to say that antipsychotics have short-term (about 6-12 weeks) effectiveness for treating schizophrenia and psychosis. But now, in his new review of the evidence, Whitaker concludes that, even in the short term, the impacts of antipsychotics in clinical trials tend to be so weak that they do not reach the level of having “meaningful” impacts on most people. Whitaker concludes, “70 years of [randomized controlled trials] have failed to provide evidence that [antipsychotics] provide a clinically meaningful benefit to first-episode patients, early-episode patients, and chronic patients.”

Personally, I wasn’t surprised. I know some people feel they benefit, but I’ve never believed that, on the whole, the drugs are truly helpful to most people—and especially not when forced on them against their will. As I discussed in Your Consent Is Not Required, other than their obvious powers to chemically restrain people, the “efficacy” of antipsychotics for “treating” schizophrenia or psychosis seems meager. In most trials, antipsychotics beat placebo only by about 4-10 points on a 210-point measurement scale. So, the numbers do consistently demonstrate a degree of effectiveness over placebo—but even without Whitaker’s more detailed analysis, to me those numbers have always seemed so small, anyway, that they’re arguably just a statistical artifact borne out of pharmaceutical bias, unblinding effects, overly subjective measurement instruments, and so on.

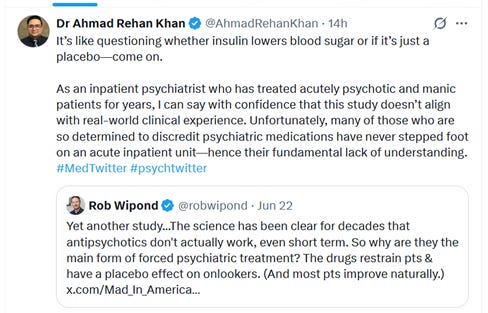

I posted a comment and link to Whitaker’s article on social media, and a revealing (and not atypical response from psychiatrists) came from Dr. Ahmad Rehan Khan, who reposted my comment to his 19K followers and said it was “like questioning whether insulin lowers blood sugar.” i.e. He did not respond to the evidentiary arguments, but just suggested that anyone who’d even ask such a question has no grasp of basic science and has lost their grip on reality.

But in fact, mainstream psychiatric researchers themselves have been showing their concern (anxiety?) about the weak efficacy of antipsychotics, even in the short term, for many years. It’s why they frequently amend their own reviews of the issue, like this one in the top journal JAMA Psychiatry, with suggestions about ways to change clinical trial methods to try to improve the apparent efficacy of antipsychotics.

Speaking of Not Helping: Civil Commitment Itself (Harms, and Recommendations for Change)

Based on interviews, information requests to government and institutions, and other research, Disability Rights North Carolina (DRNC) has released a report, "Involuntary Commitment in NC: Overused, Misused, and Harmful." (I wrote about DRNC’s powerful collaboration between attorneys and people with lived experience in a recent article.)

One hospital emergency department staff member who was quoted sums it up well: "This is almost like science fiction to me. I am watching what is happening to human beings and wondering, are we actually helping people?” A news article about the report also sums it up well: Civil commitment is a "giant sledgehammer of a tool...used for all manner of crises inappropriately” and “frequently overused and misused” while “the state is not keeping track of how often or where that is happening."

DRNC’s key findings about involuntary commitment (IVC) are potent (and unfortunately not atypical):

Lack of Due Process. People are detained in EDs under civil custody orders without appointed legal representation or timely judicial oversight. They remain in legal limbo, often for days, weeks, or months, awaiting psychiatric placement.

Traumatic Detention. Individuals—including some young children—are subjected to strip searches, physical restraints, forced medication, handcuffs and shackles in transport, and long periods in EDs, some noisy, harshly lit, and chaotic, with little to no treatment.

Harm to Families and Communities. The IVC process often excludes parents and guardians from decisions, disrupts lives, causes job loss and financial hardship, and consumes law enforcement and hospital resources unnecessarily. These damaging experiences make some people reluctant to seek out psychiatric care when needed.

Systemic Failures. The process lacks adequate data tracking and evaluation. However, from the scant data that does exist, we know that at least 63% of IVC petitions over the last six years have not resulted in actual commitments, highlighting widespread inappropriate use. This affects tens of thousands of people in NC each year.

Misuse. IVC is sometimes used by nursing homes and assisted living facilities to expel residents, by family and friends as a form of control, and by providers as a means of shifting care responsibilities—rather than addressing mental health needs compassionately and effectively.

DRNC’s main recommendations for change include:

Reduce Harm During Transport

Replace law enforcement transport with trained, non-coercive transport.

Eliminate unnecessary use of shackles, uniforms, and marked cars.

Require trauma-informed training for all transporters and give families the option to transport loved ones.

Reduce Harm in Facilities and Courts

Provide immediate legal representation once a custody order is issued.

Involve supportive guardians and children’s parents in care decisions and court processes.

Allow a parent or legally responsible adult chosen by the child to be present when a minor is strip searched.

Shorten the timeline for court hearings from 10 to 5 days.

Mandate trauma-informed care and strengthen oversight of facility practices.

Build Out Evidence-Based Alternatives

Expand peer support and non-coercive crisis response models.

Prioritize community-based prevention and treatment.

Involve people with lived experience in designing solutions. Peer support works.

Collect and Share Critical Data

Require detailed reporting on IVC processes, outcomes, and costs.

Establish public dashboards to ensure transparency and accountability.

Use data to inform policy and identify breakdowns in care.

Expanding Civil Commitment: Dementia (Are you becoming older? You’re at risk!)

A news report from the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry 2025 Annual Meeting discusses a presentation on dementia and civil commitment. The Psychiatric News article states that “there is a trend toward excluding this patient population from the civil commitment process” in the wake of a 2012 Wisconsin legal case declaring that dementia cannot be grounds for detaining people in psychiatric facilities because it’s a permanent, incurable organic condition. That may be a trend; however, details from the article reveal a somewhat different story:

In 10 states (FL, ID, KS, MI, MS, NV, OK, TX, VA, WV), people with dementia must have a comorbid qualifying mental illness.

In four states (DE, NJ, IL, MT), people with dementia are included under certain conditions, such as if they are dangerous, gravely disabled, and/or have psychosis.

Two states (MO and WA) have both above contingencies.

34 states currently have no clear exclusions of people with dementia.

18 states include language that suggests dementia might reasonably be included within the definition of mental illness, by using terms such as “disorders of memory” or “organic” disorders.

So, if you’re one of the unlucky at-risk people who is aging by the day, you may want to get some legal papers in order like an advance directive, representation agreement, power of attorney, and so on (the relevant laws/names can differ in different jurisdictions). Although, bear in mind, civil commitment usually trumps all of these—but a reasonable judge will at least still consider them.

Expanding Civil Commitment: California Goes All-in (Are you one of 86% of the population?)

Legislators in California continue to push to make civil commitment legal powers more flexible and aggressive.

As I discussed in Your Consent is Not Required, definitions of “mental disorders” in each new addition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) keep becoming larger in number and broader in scope, such that some psychiatrists now assert that as many as 50% of children and youth and more than 86% of adults will meet clinical criteria for one or more disorders in our lifetimes.

I posted last year on social media about how this trend dangerously increases everyone’s risks of being detained and forcibly treated, because being identified as having a mental disorder is step one in the process of involuntary commitment. Psychiatrists responded with various degrees of fury, disdain, and derision, pointing out – correctly – that most mental health laws use generic definitions like “substantial disorder of the mind” rather than the definitions of mental disorders from the DSM. And this is a good thing, in the sense that it can help remind judges and tribunals that they’re supposed to independently assess whether a “disorder” of the mind is truly occurring at all. I acknowledged that was an important clarification, but countered that most judges and tribunals still get heavily influenced by any DSM diagnoses that psychiatrists render (“schizophrenia” or “bipolar” are more likely to get you forcibly treated, for example, while “social anxiety” or “temporary substance-induced psychosis” are more likely to get you freed).

In any case, California legislators seem determined to resolve this debate in favor of my opinion — much to my chagrin.

Last year in their CARE Act, CA legislators added language that declared getting labeled with the DSM diagnoses of “schizophrenia” or “other psychotic disorders” would qualify people for potential coercive treatment and guardianships under the Act. Now a new California bill proposes to expand that to include “mood disorders with psychotic features” as well, and the bill explicitly specifies: “as defined in the most current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.”

And incidentally, that’s actually a massive expansion of who can be caught under the CARE Act. “With psychotic features” is a not-uncommon diagnostic add-on to depression, anxiety, or other common “mood disorders” when a psychiatrist feels a person is displaying, say, delusional beliefs because their depression or anxiety is not rooted in an issue the psychiatrist considers to be reasonable.

Yet California legislators aren’t stopping there. Another bill will expand the step-one criteria for civil commitment to include any of the hundreds of conditions “in the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.” (Disability Rights California has started a Substack column and the first post discusses these and other painful new bills.)

So, could millions of people in California get locked up for caffeine disorder or internet gaming disorder? Or what about for Narcissistic Personality Disorder—surely, having “grandiosity” and a “need for admiration” are nearly universal survival strategies in places like Hollywood, Los Angeles, and Silicon Valley! Now I imagine many psychiatrists would say I’m just being foolishly inflammatory—but if so, then why are they allowing these “disorders” to be embedded into civil commitment laws?

I was just looking at an article yesterday about people who take SSRIs are at higher risk of dementia.

Lock people up, give them dementia with the pills, lock them up again once they get dementia.

These laws look like we're entering a state of totalitarianism...

It is beyond distressing to see formally progressive states (such as California and Oregon) passing these highly regressive laws. This certainly brings to mind the famous quote from Germany in the 1930s about how “they came for” various groups, and no one spoke up against it, and then when many people finally realized how vulnerable they were, there was no one left to defend their human rights, and offer protection. Thank you, Rob, for stating the facts so clearly, and sounding the alarm.