Texas Finally Has an Involuntary Commitment Law!

And other asinine and misleading news reports from around the nation (PsychForce Report News Roundup Sept-Oct 2025, Part 3)

Breaking news!

A groundbreaking Texas bill authorizes police to take people to psychiatric hospitals against their will.

State lawmakers pledge to create “new,” expansive commitment laws in Washington that the state already has.

Witnessing the manifestation of its own vision for mass commitments, the New York Times blames it all on Trump.

AI can now predict, more reliably than humans can, the existence of mental illnesses that don’t exist yet.

ProPublica reports on the tragedies caused by anyone questioning psychiatric diagnoses.

The Marshall Project blames too many people being forcibly detained on not enough people being forcibly detained.

No, it’s not April Fools on PsychForce Report. In this third and concluding installment of the September-October 2025 news roundup, I review a selection of prominent news reports that aptly illustrate how and why public discussions of civil commitment end up so far from reality. And I highlight some of the key questions that we should all be asking journalists and legislators to ask.

According to this report from Spectrum News 1, a statute passed earlier this year in Texas “will allow law enforcement officers to detain without a warrant those who they believe are at risk of harming themselves or others due to mental illness.”

So… Texas is the last jurisdiction in America to finally get an involuntary commitment law on the books?!?

No. And the article doesn’t get much more accurate further in. Apparently, the staff journalist and her editor didn’t read the bill they were reporting on, let alone notice the main actual change enacted, though it was highlighted seven times in neon-green.

ABC News got it a little righter, reporting that the new Texas law “lowers the bar for police intervention.”

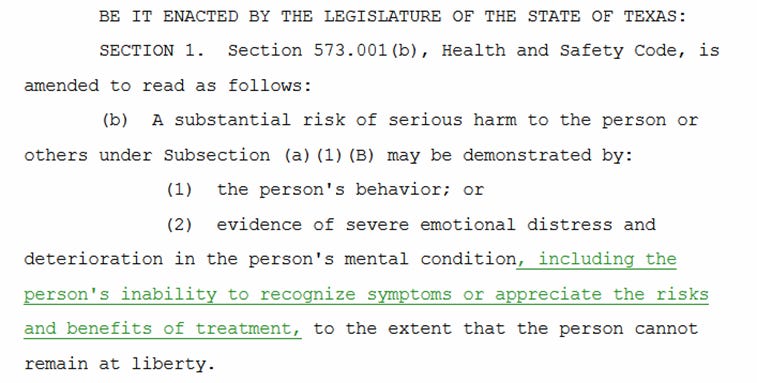

Yes. And it does much more than that... In fact, Texas Senate Bill 1164 introduces a whole new criterion under which someone can be detained by police and involuntarily committed by physicians to a psychiatric hospital. In doing so, it made the state’s civil commitment statutes some of the most broad and aggressive in the country.

Most states’ mental health laws authorize police to initiate psychiatric detentions and physicians to commit people to a psychiatric hospital if you appear to be experiencing some kind of disorder of the mind and are physically endangering yourself or others. Even that kind of risk of harm or danger is often broadly interpreted. But under Texas law, a person is now deemed to be at “substantial risk of serious harm” to self or others, and can be psychiatrically incarcerated, if the person is simply in “emotional distress” and appears to have an “inability to recognize symptoms or appreciate the risks and benefits of treatment.”

What does this mean in a real-world context? Essentially… if Texas police can see that you’re experiencing emotional distress, but you say you don’t think you’re mentally “ill” — you’re dangerous and can be detained. If Texas psychiatrists believe you’re in emotional distress, yet you don’t agree with their recommended treatments—you’re dangerous and committable.

The ABC News article made it clear that pro-force lobbyists from the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) were among those behind this extreme broadening of the criteria for detention and commitment. The article also quoted ex-patient and now government mental health rep Eric Smith saying the new law “will save lives,” and describing how a forceful intervention once helped him. Perplexingly, Smith then added that the law did need safeguards. “I’m terrified of the prospect of people’s freedoms being infringed upon,” Smith said.

Sorry, Mr. Smith, but this bill pretty much plowed over the safeguards—and news reporting like this is a big part of the reason that can happen.

Smith’s and Spectrum News 1’s kind of confusion is not uncommon, and is all too frequently exploited by the likes of NAMI. Conversely, this article in the Seattle Times appears to be a genuine attempt to investigate, expose, and clarify some of the frequent confusions, conundrums, and conflicts that emerge in public policy debates about civil commitment. Tellingly, the journalist noted:

“Lawmakers, health officials and the governor have all said they’d like to revamp the involuntary treatment system. But many of the changes proposed in these discussions have already been passed into law over the last decade… The state has laws on the books to lower the threshold for committing people, expand treatment for people with substance use disorder and improve community-based treatment options.”

That’s a helpful observation—and sadly typical of the unrealities at the center of too many public policy discussions about civil commitment.

Incidentally, the journalist also reported, if you’re in Washington state, “A group of attorneys, mental health professionals and law enforcement officials from around the state is now spearheading a ‘listening tour’ it hopes will inform recommendations to legislators for the next session. The ‘ITA task force’ is traveling the state and interviewing people who have gone through involuntary treatment, as well as those who work in it, to identify broad complaints.”

A plan is rapidly gathering political support in Utah for a sprawling, gated, guarded detention area for unhoused people in the remote desert. According to news reports, (see stories here and here), this so-called homeless “campus” would hold 1,300 or more people, and include a huge on-site civil commitment facility, dubbed by its promoters as an “accountability center” for misbehaving homeless people to get, they say, “healing.”

Utah is already the North American capital of forced treatment for children and youth (often dubbed the “troubled teen industry”), so this isn’t likely leading anywhere good…

Two New York Times journalists then covered the story, headlined “In Utah, Trump’s Vision for Homelessness Begins to Take Shape.” Seemingly somewhat perturbed by what they were witnessing, NYT staffers Ellen Barry and Jason DeParle repeatedly blamed it all on Trump’s executive order calling for more civil commitment of homeless people.

Is this a political turning point for Times coverage of these issues, then?—Almost certainly not, since the journalists never once give even the slightest nod to a mea culpa about their own and the Times’ years of articles that feature dehumanizing characterizations of people living on the street and calls for rebuilding large psychiatric institutions to hold them.

According to a number of articles (e.g. here and here), a team of Duke University researchers have developed an AI tool that can predict, with “84% accuracy” which adolescents are “most likely to develop a mental illness within a year”—which helped the researchers pull in a $15 million grant to scale their work into real-time tracking of thousands of young people.

Since no humans can do such predictions with anything close to such accuracy, if this were true, it would qualify as Nobel Prize-winning research both for medicine and for AI development. But…

No.

The study itself clarified that the AI tool wasn’t predicting anyone’s mental illness. The AI was mining the details of kids’ medical and therapy records and labeling those who appeared to be moving from a “lower-risk” group to a “higher-risk” group. And the alleged accuracy was achieved by the researchers adjusting the AI tool to land on similar assessments as the most common mental health screening tests do—which even proponents of such tests recognize “diagnose” incorrectly many times more often than they “diagnose” correctly (see the sensitivity and specificity scores).

Btw, in case you’re wondering, the top finding the AI uncovered was that kids tend to do less well when they aren’t sleeping—I bet you parents out there would never have guessed that! But, seriously, these kinds of misleading claims of predictive accuracy need to be exposed, because they give massive boosts to calls to expand aggressive “early intervention” efforts and the forced treatment of minors.

I appreciate much of ProPublica’s investigative work, but not so much their ongoing series on health insurers denying people’s mental health claims. This latest story, and an earlier one that exposed some of the on-call psychiatrists who help insurers deny people’s mental health claims in court, are indeed heart-wrenching—it’s sad to see people in serious distress not able to access whatever kind of assistance they find helpful. However, after many months of stories on this general problem, not once has ProPublica explored the core, driving issue: Why is it so easy for health insurers to use expert witnesses to successfully undermine mental disorder diagnostic and treatment claims?

The answer is that most mental disorder diagnoses and the psychiatric treatments for them, unlike most health diagnoses and treatments, are extremely unreliable and arguably remain unscientific—as even DSM5 experts writing in the American Journal of Psychiatry have debated.

I and others have reached out to ProPublica to draw their attention to this, but seem to have had no impact. The unfortunate consequence is that, when these journalists treat psychiatric diagnosing as if it’s scientifically sacrosanct and morally unassailable, it leads to them ignoring the flip side of the problem: the bogus diagnoses, debilitating treatments, and broad involuntary commitment laws being used for fraudulent insurance billing.

The Marshall Project has a similar problem, albeit with a different issue. They specialize in nonprofit journalism about the criminal justice system, and recently put out a new report on the long backlogs of people around the country getting caught for months or years in prison-limbo, never getting their day in court, after they’ve been declared mentally “incompetent to stand trial.”

This issue gets a lot of media attention—and is often alluded to as America’s “competency crisis.” Yet journalists rarely if ever seem to ask why – instead, even the Marshall Project article simply quotes, unchallenged, the Treatment Advocacy Center refrain that the problem is failing to forcibly treat people who therefore, tragically, commit serious crimes.

That can sound vaguely plausible, so… no evidence required.

However, there’s no evidence forced treatment prevents crimes and, more importantly, there’s no evidence that the majority of these rising numbers of people being declared incompetent are in fact committing serious crimes. Increases in the numbers of incompetency declarations are also occurring among people being charged with simple crimes or misdemeanors related to homelessness or disruptiveness, like trespassing, drug use, disturbing the peace, traffic violations, shoplifting and so on.

Other countries do not appear to have comparable numbers of people or levels of backlog in their forensic psychiatry systems. So the real question is: Why are U.S. judges, prosecutors, defense lawyers, and competency evaluators increasingly deeming defendants to be mentally incompetent to stand trial? What’s really going on?

Some American specialists in the field suggest that Americans are becoming crazier. I’m wary of this “blame the victims” approach that starts from the presumption, once again, that psychiatric diagnosing is essentially infallible science. So, I don’t have the answer, but I’m investigating—feel free to share your evidence, thoughts, and theories with me!

I’m commenting on the part about forensic psych institutions. A few things are being mixed together. 1) competency to stand trial 2) the right to refuse drugging that psychs want to do to ‘restore competency’ and 3) the overall agenda to drug people as a response to crime. I won’t go into all the human rights that is violating right now but just say it’s interesting that the question of actually having a right to be deemed innocent until proven guilty has gone out the window.

I think it’s time we face the mounting evidence as we also reflect on history. From Ancient Rome on, elite leaders have always used propaganda to make force and even genocide look like it’s for the good of humanity. Why would we think anything is different now?

Because we have democracy now? Didn’t they have democracy in Ancient Rome? For a while?

History doesn’t just repeat itself it never changes the theme nor the plot.

This is our world—a few control all the resources and so they must keep the many from rising and taking it—and it’s always been this way. The few are just really good at tricking the many into thinking this is the modern era, things are different, we have all evolved...