"Lock 'em up!"--Without Thought

Two high-profile op-eds show how pro-force conservatives and liberals alike use the same ideas and rhetoric

An op-ed by Jason Sorens of the conservative American Institute for Economic Research published in the conservative National Review provides a case exemplar in how involuntary commitment often gets misleadingly promoted as a grand solution to homelessness, mental illness, and addiction. Notably, a recent op-ed in the liberal-leaning New York Times (also available here) by Stanford University psychiatrist and former Obama advisor Keith Humphreys does much the same thing, in much the same ways.

Indeed, the biggest difference between pro-force liberals and conservatives that I’ve seen on this issue—illustrated amply in these op-eds—is that liberals tend to sound more patronizing, and conservatives a bit nastier. Other than that, the similarities in these two op-eds are striking—and worth making note of, for anyone trying to understand and/or counter common views on involuntary commitment.

Because the weight of evidence punches deep holes in their positions, pro-force advocates tend to rely heavily, consciously or unconsciously, on rhetorical techniques that discourage rather than support critical thought. I’ll compare the op-eds side by side, and discuss some of these common “thought-suppressant” techniques. A quick overview:

Ignore patients’ critical views as if they’re not worth a thought

Use false dichotomies that discourage thought

Dismiss countervailing science, or even science itself, as not meriting thought

Foster thoughtless prejudice

Encourage thoughtlessly ignoring the real problem

Unthinkingly adopt Orwellian doublethink

Actively promote Orwellian doublethink

Promise fantastically wonderful involuntary commitment practices—without thought to implementation

One: Ignore patients’ critical views as if they’re not worth a thought

In acknowledging resistance to increasing involuntary commitments, Humphreys points to an “activist” who called forced treatment “horrific.”

For his part, Sorens says that increasing involuntary commitment would “raise the ACLU’s hackles.”

Neither Humphreys nor Sorens mention the much more important—indeed crucial—vast numbers of people who’ve actually experienced involuntary commitment and how they often describe it as horrific. In the characterizations of Humphreys and Sorens, concerns about very real violence and human rights abuses get reframed as just empty billboard chants from paid activists.

Two: Use false dichotomies that discourage thought

Sorens says that forced treatment is “the only compassionate solution for people who cannot care for themselves”—and never mentions any other possible solutions.

Humphreys says that “the alternative” to forced treatment is “life on the street”—and never mentions any other possible solutions.

Such false dichotomies are core to pro-force arguments—and serve as a calculated way to sidestep the real problems and possible solutions (see also technique number five).

Three: Dismiss countervailing science, or even science itself, as not meriting thought

If he even knows it, Sorens simply ignores the fact that there’s no reliable scientific evidence to show forced treatment helps people.

Conversely, Humphreys acknowledges that there’s “a lack of high-quality evidence” to support his pro-force position. But he then dismisses that science, because “none of those studies compared the results of involuntary treatment with the results of getting no treatment”—i.e. none of the studies accepted his false dichotomy that forced psychiatric treatment is the only alternative to living a brutal life addicted on the street.

Four: Foster thoughtless prejudice

Using addiction as his example, Humphreys writes that addiction “saps” people’s autonomy and “good judgment” and their ability to “make decisions that benefit them.”

Similarly, Sorens says that “the insane” and destitute homeless “cannot exercise the same rights that sane, competent adults enjoy.”

Of course, there are countless things that can and do profoundly and negatively affect anyone’s judgment, decisions, and competency—sometimes very dangerously in relation to their own or another’s wellbeing—from misplaced impassioned love and ruthless greed to disastrous investment habits, obsessions with risky sports, over-consumption of misinformation-journalism, and… how many more do we list? But neither writer would propose locking up and forcibly treating all of the people suffering through those experiences—unless a psychiatrist retrospectively labels them as having had a serious mental disorder that drove them to it, we’d presume.

Well-meaning or not, it’s just prejudice, pure and simple.

Five: Encourage thoughtlessly ignoring the real problem

Both writers describe how distressing, brutal, tragic, and dangerous living on the streets can be—and then present confinement in hospital as the better solution.

But the brutality of living on the street—for virtually anyone, “mentally ill” or “addicted” or not—is the real tragedy. And it requires honest discussions and real solutions.

For example, they could be talking about more robust social security income, encampment opportunities in good locations, universal access to public health care, quick pathways into multiple types of independent or supportive long-term housing, and so on. But discussing the real problem and the current shortage of real solutions getting implemented would quickly bring the discussion towards recognizing the sweeping failures of our economic system rather than towards blaming its victims—and neither of these writers appear to want to go there!

Six: Unthinkingly adopt Orwellian doublethink

Sorens describes “nuisances” like “public drug use, public defecation, aggressive behavior, littering, and theft” and “homeless people screaming obscenities,” while Humphreys describes the “aggressiveness” of people using drugs and frustration about businesses “overrun” by homeless people.

Basically, both writers seamlessly pivot from their shows of compassion to exhibiting their frustration , fear, and anger. They hold two mutually contradictory ideas in their heads at the same time, and imply that you should do the same: To forcibly police people whom we dislike is also to be lovingly compassionate towards those people.

Seven: Actively promote Orwellian doublethink

Humphreys states, “Mandatory treatment that gives people their good judgment back is a restoration of their autonomy, not a violation of it.”

Sorens also writes that “Committing severely mentally ill people, those unable to care for their basic needs, into treatment does not violate liberty: it secures it…”

No: Imprisonment is not freedom. There are good reasons that Orwell flagged the dangers of manipulating language so much that we start claiming war is peace. Although one can sometimes lead to the other, and both may sometimes include elements of the other, there are still very important differences between warring and peace-making. Yes, some people do feel treatment, even coercive interventions helped them, but they’d also usually be the first to point out that it’s vital not to just gloss over as irrelevant what happened along the way, and how it happened.

Eight: Promise fantastically wonderful involuntary commitment practices—without thought to implementation

At the conclusion of his shilling for involuntary commitment, Humphreys advises us that we must simply ensure that the forced treatment we implement is of the “right quality” and “properly” and “thoughtfully” carried out in “safe and respectful” ways using the “best evidence.” It sounds reassuring—except Humphreys doesn’t provide any details about what these words actually mean in this context or about how to apprehend, lock up, strip, drag through withdrawal and/or forcibly inject protesting people in such very nice, right-quality ways. And, of course, eight paragraphs earlier in his screed, he himself already dismissed the idea of using the best-available scientific evidence as a guide (see technique number three above).

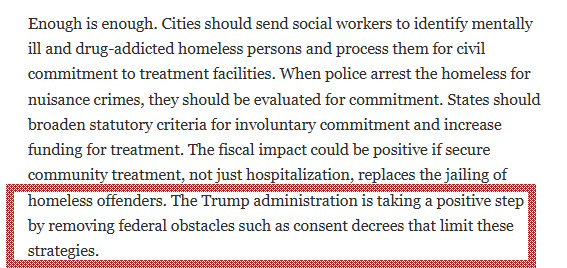

Similarly, Sorens writes that “we must not return to the bad old days” when involuntary commitment was clearly abusive. And how can this be ensured? Sorens reassures us that, when regulators fail, the federal government can still “sue states that violate the rights of… the civilly committed.” However, just four paragraphs earlier, Sorens applauded President Trump’s recent executive order for “removing federal obstacles” such as legal “consent decrees” that have slowed expansions to involuntary commitment—that is, Sorens celebrated the removal of the very consent decrees that are the federal government’s main enforcement tool when it sues states for violating the rights of the civilly committed.

In so many ways, Sorens and Humphreys ultimately don’t seem to give a lot of thought even to what they themselves think. And that is how pro-force arguments often work—by helping us not think, too.

Just as I suspected: liberals sugar-coat their fascism, and conservatives don't bother! More and more these days, the dear old New York Times, which I used to read it with interest when I could get my hands on it, is making me sick on this and just about every other subject - most notably Israel's ongoing genocide. Status quo crud.

I hope Sorens and Humphreys, or one of their relatives, don't encounter any problems that make them desperate, and thereby make them vulnerable to the horrible things they are suggesting.