988, Policing, and Force

New reports yield insights into how often 988 call centers initiate coercive “emergency interventions”—and how much is still being hidden.

Three recently released reports provide insights into 988 Lifeline’s practices of so-called “emergency interventions.” These interventions often result in unwitting callers getting calls traced, police visits, and forced psychiatric hospitalizations—practices which many users of 988 have described as a shocking betrayal of confidentiality, frightening, and traumatizing.

One of the reports emerged from a two-year Trans Lifeline investigation of 988, and is comprehensive and damning.

The other comes from the administrators of the 988 Lifeline themselves, Vibrant Emotional Health (VEH) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Their “white paper” is presented as a first step towards increased public transparency about these emergency interventions—and exposes ubiquitous idiosyncratic decision-making and poor data practices at 988.

A third new report, from NRI, the research arm of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, reveals that VEH and SAMHSA appear to still be hiding the true, rising rates of these interventions.

“The Problem with 988”

For their report, “The Problem with 988: How America’s Largest Hotline Violates Consent, Compromises Safety, and Fails the People,” Trans Lifeline’s “Safe Hotlines” project team drew on publicly available information about 988, consulted with researchers (including me), and surveyed or interviewed more than 200 people with lived experience of “mental health crises” and hotlines. Although produced prior to the VEH white paper, the result is still a uniquely comprehensive review of what’s publicly known and not known about 988 Lifeline policies and practices, covert recording and sharing of conversations, rates of policing interventions on callers, impacts of forced hospitalizations, and more.

Regular readers of my reporting on 988 will be familiar with much of the content—but there are also new insights, especially from 988 callers themselves. (I refer to all contacts via phone, text, or chat as “calls” or “callers.”)

For example, under 988 Lifeline’s “imminent risk” policy, call-attendants must, within the first five minutes, screen every caller for feelings that they might take their own lives in the near future—and then potentially contact 911 to dispatch emergency services such as police and/or ambulance to the caller’s location. Many callers explained to the Safe Hotline researchers how these imminent risk assessments render 988 virtually useless for meeting 988’s own stated core purposes.

Firstly, no one who is acutely suicidal can feel safe opening up—on the contrary, they often must pivot to reassuring call-attendants who get “triggered” upon hearing certain key words. As one caller explained, “It’s really frustrating ‘cause I struggle with chronic suicidality, but it’s not dangerous. It’s in order to prevent it from becoming dangerous that I call these hotlines. But it just sucks that less-trained folks hear the word ‘suicide’ and they become activated to behave in a certain way. And it’s just like, oh my God, this is my time to call you. Why do I have to take care of you now?” One caller described this process as having to give “a performance and a reassurance” for call-attendants, and another caller described how the conversation “becomes about managing [the operator’s] emotions and their concerns.”

Secondly, many callers pointed out that, ironically, the very people who most want and need 988’s services therefore often cannot get them—because if they talk openly about feeling acutely suicidal, they’re likely to get a police visit and forced hospitalization rather than a supportive conversation. “I always have to preface my calls with, ‘No, I’m not a danger to myself or others,’ even if I am actively suicidal, so they don’t call the cops,” said one caller. “But then you have to communicate that you're in just the ‘right amount’ of danger so that they don’t hang up or deprioritize your call.”

“I think it would be really helpful for me to have acknowledged how I was actually feeling in those moments,” said another caller. “But I just know that if you say yes to those questions [about self-harm]—those questions aren’t to have a supportive conversation. Those questions are to involuntarily hospitalize you or call the police on you or do something that isn’t helpful and is really traumatizing and harmful.”

As rich as their report is with such details, the Safe Hotlines team was unable to wrest any new information from VEH, call centers, or SAMHSA. Much like SAMHSA has done with me and other researchers, SAMHSA (illegally) delayed two years before responding to Trans Lifeline’s freedom of information requests. And then (again, illegally), SAMHSA provided no information about emergency interventions—despite having such information in its possession.

How do we know SAMHSA did in fact have such information? Grants had gone out to call centers to collect data on their emergency interventions, and SAMHSA had commissioned a study of the issue from Vibrant Emotional Health.

“An in-depth Analysis of 988 Imminent Risk Data”

In September, VEH and SAMHSA released a “white paper” titled “What Happens When People are Actively Suicidal? An in-depth Analysis of 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline Imminent Risk Data,” written by VEH researcher Christopher Drapeau.

Why did they finally publicly release this data after years of stonewalling? Drapeau points to a 2023 Pew Charitable Trusts/Ipsos Poll that found more than 40% of Americans are wary of calling 988 because they’re concerned about potential unwanted visits from law enforcement and forced hospitalization.

Those numbers do seem stunningly high. In light of the widespread advertising and positive media coverage of 988, promotions by mental health organizations, lack of proper disclosures by call centers, and dearth of critical reporting about the involuntary interventions, how did 40% of the US population even learn about these risks? Should we credit social media users?

In any case, Drapeau writes that the goal of VEH is reactively to “increase transparency and public trust in the Lifeline's standards and practices.” And then his paper mainly does the opposite.

(Note: Since I began reviewing the published Vibrant Emotional Health paper, some of the paper’s more critical comments have been edited or deleted. For reference, I posted the copy I’ve quoted from here.)

What the 988 data shows—sorta…

Drapeau’s paper reviews all of the studies and data on emergency interventions at the Lifeline, historically and up to 2023—except for one. (More on that crucially ignored study shortly.)

Drapeau arrives at the estimate that roughly 1% to 3% of all callers to 988 get subjected to emergency interventions. And as 988 Lifeline representatives always do, he belabors the talking point that this is “only” about 2%, a “rare” event of “low likelihood” that’s merely “a small fraction” of 988’s total call volume.

It’s important to pause here. Even at these rates, based on about 5 million total contacts to 988 in 2023, that’s currently 50,000 to 150,000 people each year. Two percent is one in fifty callers—if one in every fifty airline travelers every day were getting pulled aside by security and taken to psychiatric hospitals, would we be downplaying these as nevertheless “rare” occurrences?

And unlike VEH, SAMHSA, and some commentators, I don’t feel it’s especially relevant that about half are purportedly “voluntary” and “collaborative.” As is confirmed in Drapeau’s paper, “collaborative” often has many coercive grey areas—it can simply mean that you finally “agree” to allow police to come take you to a psychiatric hospital rather than, say, smash your phone and make a run for it. True voluntary choice cannot exist alongside the threat of involuntary intervention—it’s like pointing a gun at someone and then saying they “consented” to being robbed.

I also don’t believe we should ascribe undue significance onto which emergency first responders get sent out, whether it’s the police, sheriff, ambulance, paramedics, or fire department. Unarmed responders definitely won’t shoot people, so that’s good. Beyond that, by many reports, police often accompany the ambulances, anyhow—and that’s not captured in the data. And all of these are, fundamentally, still policing interventions—the responders are dispatched to take people to psychiatric crisis centers or hospital emergency rooms whether or not they comply.

So it’s important to acknowledge: Whatever the rates, it’s a shocking, horrifying amount of people that these frightening events are happening to.

Moving on from there: What does the data say about what’s happening to these people? And are the numbers reliable, or a smokescreen disguising something much worse?

What the data doesn’t show

Drapeau himself acknowledges the “ambiguity” in the definition of “imminent risk” and the unclear, shifting circumstances under which emergency responders will be dispatched. Even “suicide attempt in progress”—the most unambiguous, tiny subcategory of imminent risk—evidently has widely varied meanings, because nearly a quarter of these DID NOT trigger emergency interventions.

Not surprisingly then, as I’ve previously reported, Drapeau confirms that different, unnamed call centers initiate these interventions at inexplicably, wildly different rates—varying as much by factors of 10, 20, 40 or more times.

And not 2%, but anywhere from 20% to 50% of the people who call specifically to discuss serious suicidal feelings get policing interventions.

All of these ambiguities and inconsistencies, Drapeau admits, decrease “the trustworthiness of imminent risk data and the insights generated from them.” This problem is compounded by shoddy record-keeping throughout the 988 system. Drapeau repeatedly amends the numbers with comments about how he struggled with inexplicable duplicate data, self-evidently incorrect data, “differences in how data are collected and reported across the 988 Lifeline network,” and “a significant amount of missing data.”

This created, Drapeau writes, “a challenge in understanding the true prevalence of emergency service dispatches” and rendered him “unable to have confidence in the integrity of aggregated imminent risk data.”

Good marks for honesty! (Although sometime subsequent to publishing, “unable to have confidence” was deleted from the paper.)

And what ultimately happens to the people who get subjected to these emergency interventions? Does 988 “save lives” as promoters claim, or instead more often destroy lives? The VEH paper offers no data on this vital question.

Drapeau concludes (somewhat damningly, it would seem) that the 988 data leaves countless unanswered questions about “the ultimate effectiveness of crisis intervention services.”

Drapeau recommends that VEH and SAMHSA clarify the circumstances under which emergency responders will be sent out, and improve data collection about how often it happens and to whom, and about what impacts it’s having. However, it’s difficult to be carried far by his carefully edited stylistic posturing that this disastrous mess nevertheless optimistically represents a “significant opportunity” for “refinement” and “quality improvement”—especially when internal and external critics have made the same recommendations in vain over twenty years, and these problems have endured through visibly large turnovers in VEH senior staff the past two years.

Indeed, by this point, regular readers of my reporting on 988 might also be thinking: Wait a second… What happened to the largest and most comprehensive data collection effort ever done on U.S. crisis hotline emergency interventions, which showed dramatic increases occurring?

As I reviewed the VEH white paper, I wondered the same thing.

Speaking of “missing data”…

As I reported on for Mad in America earlier this year, NRI, the research arm of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, conducted its own national survey of crisis call center emergency interventions. The NRI survey was the most expansive data collection effort of the kind ever done, gathering data on several million calls in 2022—half from 988 and half non-988 call centers. NRI found that the rate of emergency interventions was 7.8% overall—nearly a staggering four times higher than the rate historically claimed by VEH and reported in Drapeau’s paper.

NRI researcher Ted Lutterman told me that state agencies had combined 988 and non-988 data, and then had demanded anonymity when submitting to NRI—another indication of how sensitive this information is. However, Lutterman said, VEH would have 988-specific data.

I presented the 7.8% figure to VEH, and asked if their 988-specific data indicated anything substantially different. VEH and SAMHSA both declined to comment.

More recently, however, sources told me representatives of 988 Lifeline were telling questioners that the NRI report was “misleading.” And VEH started publicizing to major media Drapeau’s paper and 2% rate.

What was going on? I reached out to VEH again, and to their researcher, Christopher Drapeau.

Drapeau never responded. Divendra Jaffar, the Public Relations & Engagement VP for VEH, answered in an email, “The [VEH] white paper summarizes research specific to the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, utilizing studies and data sources that align with 988 network administrator Vibrant Emotional Health’s definitions of imminent risk data categories. The NRI survey data uses different definitions and doesn't directly compare with the Vibrant data without misinterpretation.”

So, I asked, in what ways do the NRI “definitions” differ from VEH’s? And what misinterpretations might result? I also asked why Drapeau’s white paper didn’t itself discuss these very issues—nor indeed so much as mention the NRI study. Why completely ignore this recent, expansive survey of 988 emergency interventions?

Drapeau and Jaffar declined to answer. Repeatedly.

This left me wondering… Why wouldn’t they answer?

After all, given how controversial these interventions are, if the current 988 intervention rate truly is close to 2%, surely it would only be to VEH’s benefit to explain to me—and all of us—why theirs is a more reliable number than NRI’s 7.8% rate.

Unless?…

Unless explaining why the rates were so different would reveal something else that they didn’t want to reveal?

Then, just this week, NRI dropped an update to their previous report on emergency interventions, with 2023 data—and everything became clearer.

Plus everyone else who is getting police visits…

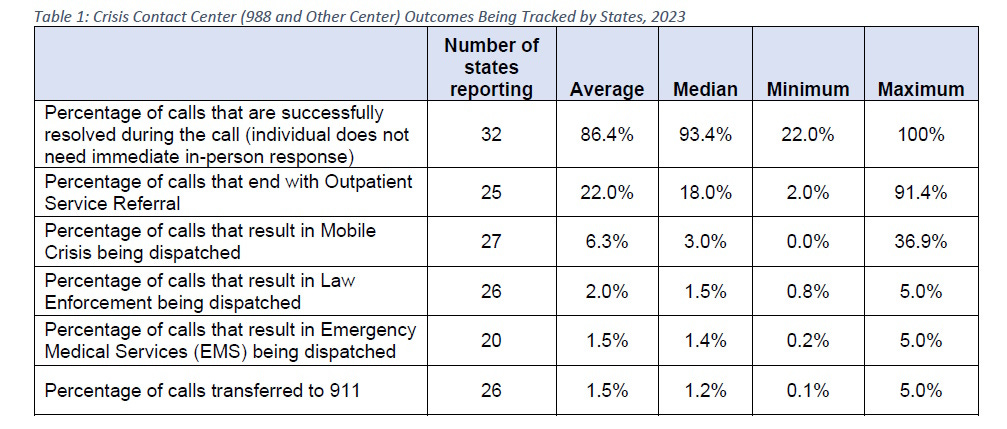

In its latest update, NRI found a 5% rate of contacting 911, law enforcement, and emergency medical services at call centers around the country—lower than in 2022, but still two-and-a-half times VEH’s claim of a 2% rate.

VEH’s data gathering likely missed not just some, but the majority of emergency interventions occurring—and for plausible reason. It appears VEH put limits on its own data collection.

Drapeau repeatedly emphasizes that the data in the VEH paper is focused on suicidal imminent risk. Jaffar also emphasized in his email to me that their data was based on VEH’s “definitions of imminent risk.” In addition, VEH’s most recent data-gathering form for call centers was titled the “Imminent Risk Data Reporting Form.” And whether intentional or inadvertent, the key section of the form appears to guide call-attendants to record emergency interventions sent out on people who were suicidal and deemed to be at imminent risk—and ONLY those people.

Conversely, NRI obtained from call centers the number of emergency interventions they initiated—period. There’s no mention by NRI of motivating reasons or categories of call types.

The NRI approach is better, because it’s well known that emergency interventions are sent out in response to many types of callers who would not typically be categorized as at imminent risk for suicide.

For example, any suspected child abuse provokes automatic contacting of police and family services (even as families and community organizations are increasingly fighting back at what they see as racist and invasive family service agencies doing more harm than good). These aren’t mentioned in the VEH white paper.

I’ve interviewed sources and read countless personal stories and social media discussions wherein callers to 988 were adamant that they were not at all suicidal—but call-attendants contacted 911 to do a wellness check because they thought the callers were in such distress or disorientation that they might harm themselves in some way. The previous Lifeline intervention policy specifically instructed call-attendants to do this. (VEH’s new guide to their safety policy is hidden from public access.)

People who express feelings of wanting to harm others also often get police visits. The appendix in the VEH white paper suggests that these interventions are separately tracked by some call centers—but Drapeau never discusses that data.

There are also third-party calls—according to a 2022 study, these are approximately 25% of all calls. Millions of people contact 988 to express concerns about someone else—and these lead to emergency interventions at higher rates than when people contact 988 about themselves. It’s unclear in the white paper if VEH is truly capturing all of these, or just some of those related to people at imminent risk of suicide.

Including all of these and other types of calls presumably explains why the true rate of interventions is much higher than VEH claims.

A further indication that VEH and SAMHSA seemingly want to create ways to count fewer interventions: Drapeau’s paper does not include current data on dispatching of mobile mental health crisis teams (MCTs), even though these are rapidly increasing in number, often sent without caller consent, and frequently involve police.

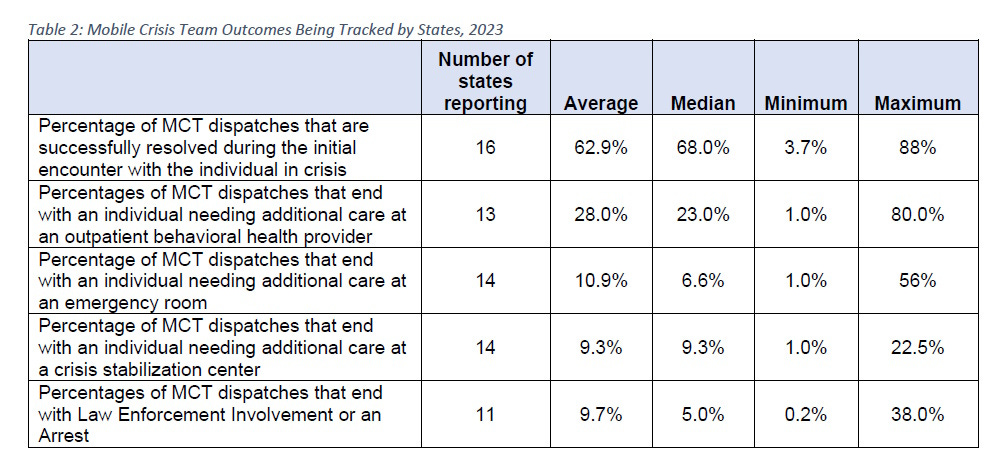

On top of the 5% rate of emergency interventions that NRI found, NRI reported that MCT interventions occurred in response to another 6.3% of all calls (see Table 1 above). Of those, 30% became the same as any other emergency intervention; that is, the caller landed in a psychiatric crisis center, hospital emergency room, or jail—a third of the time taken there by police (see Table 2 below).

If we were to count only this last group of callers who got taken away by police, they alone would add another 2% to the total rate of 988 emergency interventions.

In conclusion, the NRI data appears to better capture the real, overall number of emergency interventions occurring through 988. At the low end, it’s 5% of all calls, or two-and-a-half times what VEH claims. At the higher end, including some or all of the MCT interventions, the rate is 7% or even 11.3%--three-and-a-half to five times higher than VEH claims.

So, these often-traumatizing policing interventions—at least half of the time explicitly done without any level of consent—affected between 250,000 and 565,000 Americans last year alone. These are numbers almost difficult to grasp, making 988 seem more like a mass-scale covert policing operation than a confidential help line.

And these dramatic increases appear to have occurred since the launch of 988. This is why it’s so vital that VEH and SAMHSA acknowledge them and invite internal and external public discussion about what’s really going on at 988 and how to roll back this expanding human disaster.

Unfortunately, in line with a pattern of behavior that’s continued for years, it appears instead that VEH and SAMHSA are still “transparently” trying to disguise the real rates of interventions and dodge public accountability.

Apart from all of the numbers, this punctuates perhaps the most meaningful, human difference between the Trans Lifeline report, and Vibrant Emotional Health’s white paper. Unlike the Trans Lifeline researchers, SAMHSA and VEH never interview people who’ve actually been subjected to emergency interventions to try to better understand the impacts of 988’s practices—or, if they have interviewed them, SAMHSA and VEH have never shared publicly what they heard.

Thank you, Rob, for your determined fact finding, and dogged investigative journalism on a human rights issue of such importance, and wide-scale significance. The level of obfuscation, and stone walling on display is deeply concerning, and certainly erodes trust in organizations given massive funding, and the power to determine the fates of vulnerable people reaching out for assistance. May your work lead to much greater accountability, and transparency, and encourage the right questions to finally be asked (and answered!) to create a genuinely effective, and humane response to those experiencing extreme emotional distress.

this looks familiar! I need to facetime you soon!! I was take to PES and injected with Abilify! I was on oral medication. The police gave me the reports or warrants for me. They are fake dated 2017. I recorded my psychiatrist and case manager 1 hour scrambling to justify another 6 months. I want you to listen. The hospital is trying to kill me like my friend Sam. They withheld my regular medication 5 pills for 4 days. I think I died again from the combined withdrawals. This is how people are dying from psych poison .. withdrawal treated as disease progression!! let me know when we can connect?

*Kir